I needed a thread pool for a C++ project. There are a few out there1, but none are standard. I set about making my own, thinking I could strike a better balance between power and ease of use than some others have, while learning from the experience along the way. Early versions of the thread pool worked well for my application. I have now expanded its features and am happy with the results of this experiment. I will use this post to describe some of its internals.

First, you can find the thread pool on Github: https://github.com/geoff-m/worker-pool. You can read the readme or the code for a complete reference, but for the purposes of this blog post, it suffices to know that adding a callback to the pool returns a task object, and you can use that object to wait for the callback to be completed. The thread pool handles waiting in an interesting way, which is what this blog post will discuss.

What does it mean to wait?

In general, the basic contract of any function called “wait” is that it does not return until something reaches a certain state or an event occurs. The important thing is the postcondition. What happens on the current thread during the wait call is not assumed to be very interesting; most of the time is likely to be spent blocked on some mutex or condition variable. Otherwise, maybe you got lucky and found the awaited condition to be true on entry, so the wait returns early.

Although blocking the current thread until some condition is met is all a wait function typically does, I foresaw that as a problem in my thread pool, which I wanted to support waiting for tasks from inside other tasks. When a pool thread waits, it in a sense breaks the contract of the pool, which promises a certain degree of parallelism2. Your 8-thread pool isn’t really doing 8 things at a time if threads 1-4 are just sitting there waiting for thread 5-8 to finish. To the extent that waits are often inevitable in correct algorithms, the fact that we are blocking a thread is acceptable per se, even necessary. However, the problem remains that if the pool has a large backlog of work items and the worker threads are collectively spending a considerable fraction of the time waiting, then the pool is likely underdelivering on expected throughput.

Fine print: a preface to the rest of this post

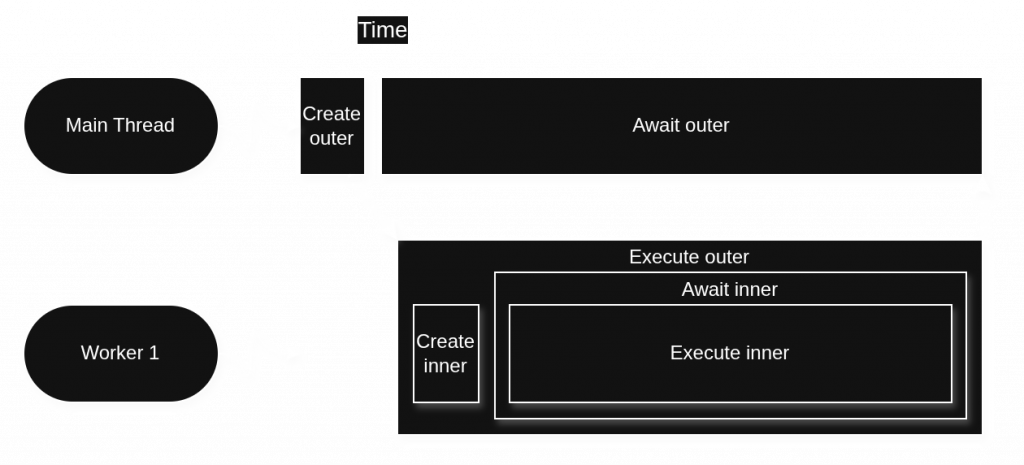

Throughout the rest of this post, I refer to threads like “Worker 1” and “Worker 2”, and I show diagrams depicting what happens at runtime. Understand that much of the specifics therein are for illustrative purposes only, as what actually happens at runtime is nondeterministic and hard to faithfully represent here without sacrificing clarity. The code discussed here does not really name or number threads, and even if it did, it would not matter which was which. Except where stated otherwise, most of what follows describes what may happen, not what must happen.

The size of boxes on timelines is only roughly to scale. For example, executing a pool callback may easily take billions of times longer than adding the callback to the pool, but I illustrate that ratio here more like 4:1 than as 1,000,000,000:1.

Dotted lines are rough hints as to the presence of cross-thread data or signal flows, such as the act of waking a thread with a condition variable, or writing data to a structure that is read by a different thread.

wait internals

When you call wait on a pool task, you block the current thread until that task is done. If wait were to be called (and not return immediately) from a pool thread, the pool’s effective parallelism would drop. WorkerPool uses two strategies to mitigate this.

Executing unstarted tasks synchronously

The first strategy is that when wait is called on a task that has not yet started, WorkerPool will use the calling thread to execute the task. This makes the “waiting” thread do something useful instead of just blocking. Consider code like the following:

pool pool(1, 0, false);

auto outer = pool.add([&]{

auto inner = pool.add([]{ sleep(1); });

inner.wait();

});

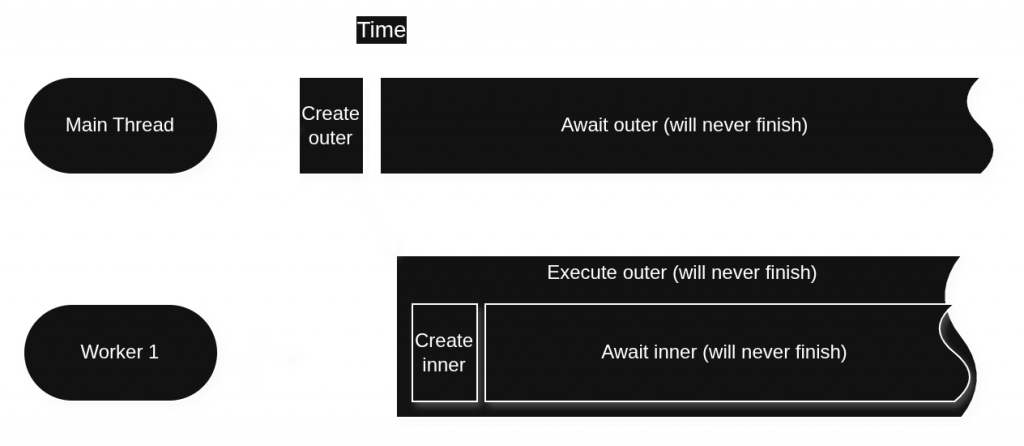

outer.wait();As the pool has only one thread, having the outer task create and then wait for an inner task seems like a sure recipe for a deadlock. But instead of just going to sleep until inner is complete, wait notices that the task it’s about to wait for is not yet started. It decides therefore to run inner synchronously on the waiting thread.

Indeed, without this strategy, this particular code would deadlock the pool, since there would be no thread available to start inner.

outer) depending on an unstarted one (inner), which would happen if there weren’t enough threads and we didn’t have this run-while-waiting strategy.In this tiny example, it happens to avoid a deadlock due to total starvation of the pool’s set of only one thread, but this is an extreme case. The main effect of this strategy is to modestly reduce the amount of time pool threads spend idly waiting. It doesn’t apply all the time, because it only works for tasks that are unstarted at the moment when they are awaited.

What about non-pool threads?

Non-pool threads (like “Main Thread” in the diagrams) also wait for pool tasks, so can they do pool work while they’re waiting too? The answer is yes, non-pool threads can help by doing unstarted pool work. I made a pool constructor option to control whether you want to allow non-pool threads to be able to do this, anticipating that some users will want all pool tasks to be done strictly on the pool-managed threads (maybe those threads are special in some way).

Using extra threads

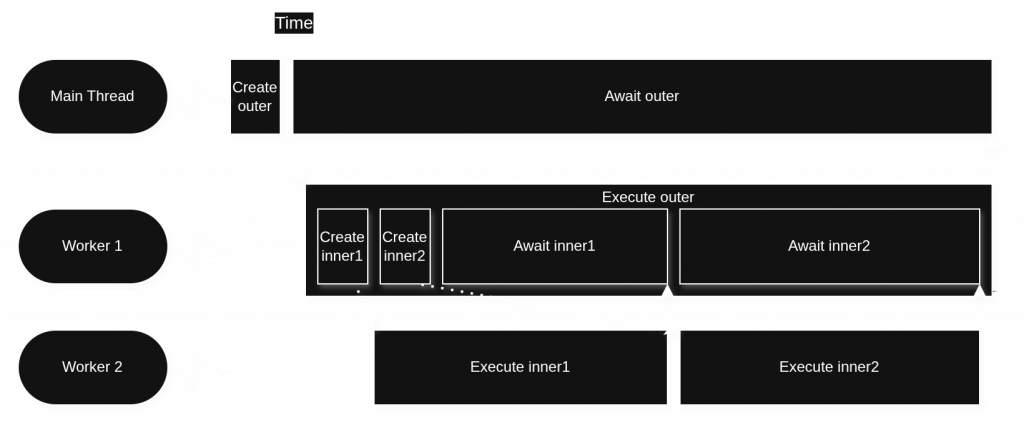

What if the task to be awaited is already in progress? In this case, the waiting thread can’t avoid simply blocking while it waits for whatever thread is doing the task to finish. When the waiting thread is a pool thread, going to sleep will cause the pool’s parallelism to drop temporarily. This is illustrated in the following example.

pool pool(2 /* target parallelism */,

0 /* extra threads */,

false /* allow running on non-pool threads? */);

auto outer = pool.add([&] {

auto inner1 = pool.add([] { sleep(1); });

auto inner2 = pool.add([] { sleep(1); });

inner1.wait();

inner2.wait();

});

outer.wait();

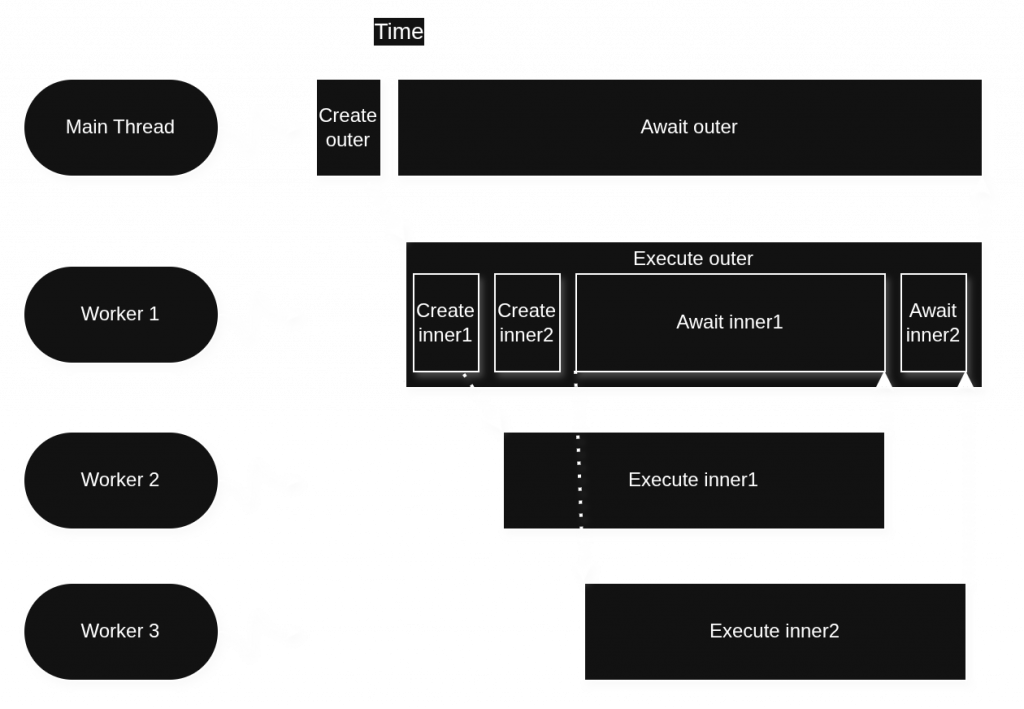

inner1 and then inner2. This pool underdelivers on the expected parallelism of 2 threads.This is where the second strategy WorkerPool uses to support awaiting tasks on pool threads comes in. When a pool thread calls wait on a task that is already in progress, WorkerPool may employ an extra worker thread in order to sustain its target degree of parallelism. If we change the extraThreads pool constructor parameter to 1 or more, the above code could behave very differently, as shown in Figure 4.

As before, when inner2 is created, no thread begins it right away, because the pool is already operating at its target degree of parallelism of 2 set in the constructor. But this time when Worker 1 begins waiting for inner1, the pool substitutes in Worker 3 so that the pool’s parallelism doesn’t drop below its target. The main limitation on this strategy is memory, which is the reason why we can’t just create a new thread every time ad infinitum whenever we wait for an in-progress task.

An astute reader may have noticed that if only this example program had been better written, the extra thread wouldn’t have been needed. In particular, if the program had said to wait for inner2 and then inner1 (reversing the order), then Worker 1 could have done inner2 synchronously while Worker 2 was doing inner1, and there would be no need for Worker 3. The wait_all function helps automatically address this issue and is described below.

wait_all internals

In addition to the wait function discussed above, the worker pool also offers a wait_all function which waits for a collection of tasks to become complete. How do you think this is implemented?

template<typename Tasks>

void wait_all(Tasks tasks) {

for (auto& task : tasks) {

task.wait();

}

}The above implementation is appealing because it’s very simple, and it can make use of the fancy pool wait discussed earlier. However, it doesn’t take full advantage of the fancy waiting logic. Consider a use case like our previous wait example:

pool pool(2, 0, false);

pool.add([&] {

std::vector<task<void>> subtasks;

auto inner1 = subtasks.emplace_back(pool.add([] { sleep(1); });

auto inner2 = subtasks.emplace_back(pool.add([] { sleep(1); });

pool.wait_all(subtasks);

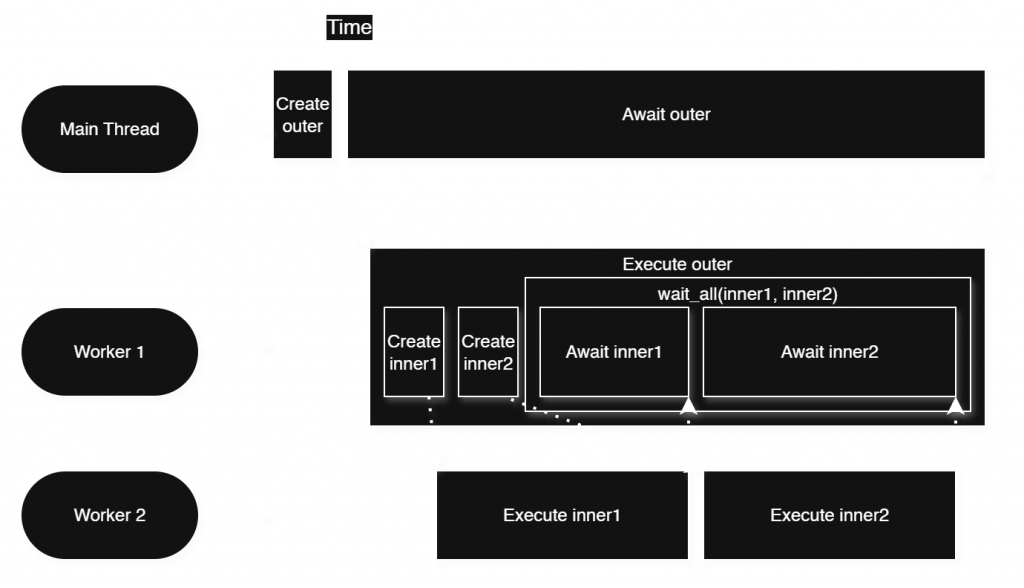

}).wait();What might happen when this executes is that Worker 1 runs the outer task, and Worker 2 begins inner1. When Worker 1 gets to the wait_all, our simple implementation tells it to wait for each task in order, so first we wait for inner1. inner1 is already in progress by Worker 2, so we block until it finishes. When Worker 2 finishes inner1, we resume and wait for inner2. inner2 has either not been started, or has just now been started by Worker 2. In either case, we are going to have to wait for inner2 to transpire before the wait_all is complete.

wait_all.The above timeline illustrates how outer takes at least as long as inner1 running in series with inner2. Unlike shown where Worker 2 does it, Worker 1 could run inner2 synchronously instead, but that would not change the finishing time. However, if we had a different algorithm for wait_all, we could have gotten a better result by executing inner2 while inner1 was in progress.

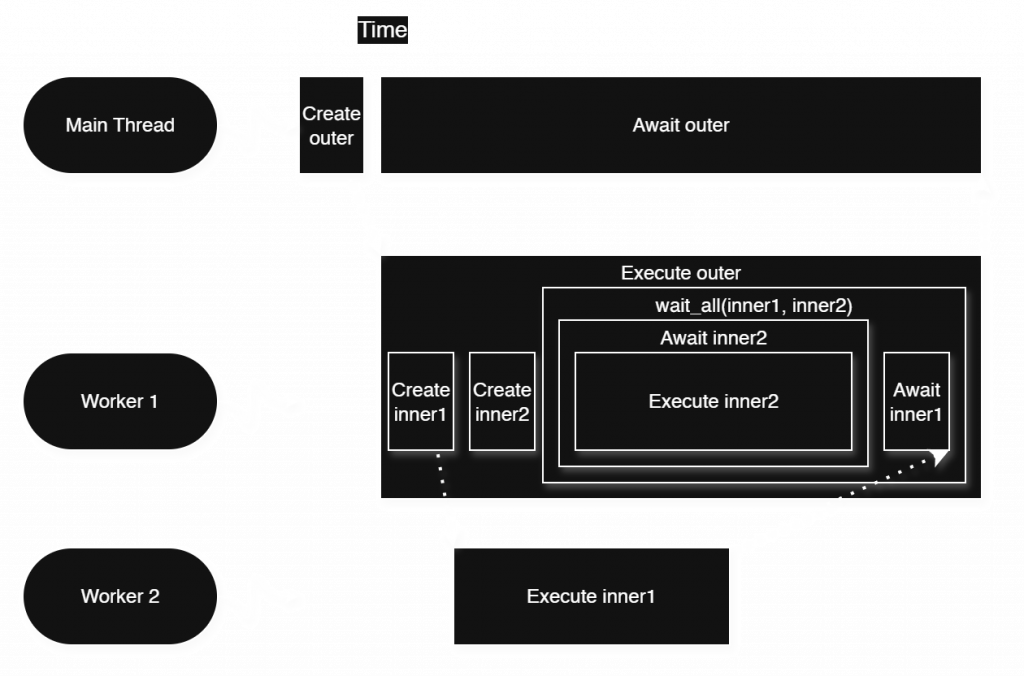

How could we arrange for wait_all to do this? Simply search the given collection of tasks for any that can be executed synchronously, i.e. which are unstarted, then execute them. Wait for any in-progress tasks only at the end, when there are no more unstarted tasks to be awaited.

wait_all.Notice how the improved algorithm overlaps the execution of inner1 with that of inner2, thereby achieving a lower overall latency. The improved wait_all does inner2 first because it’s unstarted, and by the time inner2 is complete, waiting for inner1 is effortless since Worker 2 has already completed inner1.

Timed waits

Finally, a note on the timeout-supporting versions of the wait and wait_all functions (wait_for, wait_until, wait_all_for, and wait_all_until). These differ little from the untimed versions, except when it comes to synchronous execution of unstarted tasks. Since we don’t know how long a task will take, we must not attempt to run a task on the waiter thread, as it may turn out to take longer than the timeout should allow. There are theoretical alternatives to this, such as having known time bounds on tasks, or a mechanism to move an executing task from one thread to another, but these are too restrictive and/or complex to be worth adding to the design. Therefore, we simply avoid that technique in a timed wait, instead waiting for some other thread to do all the work we’re waiting for. Meanwhile, the technique of temporarily adding an extra thread is equally safe and useful as for untimed waits, so timed waits still use it.