WorkerPool, the modestly named thread pool I wrote about earlier has a new feature to help root out bugs: it can stop you from using the wait functions to cause a deadlock. This post will discuss how this feature works.

The idea

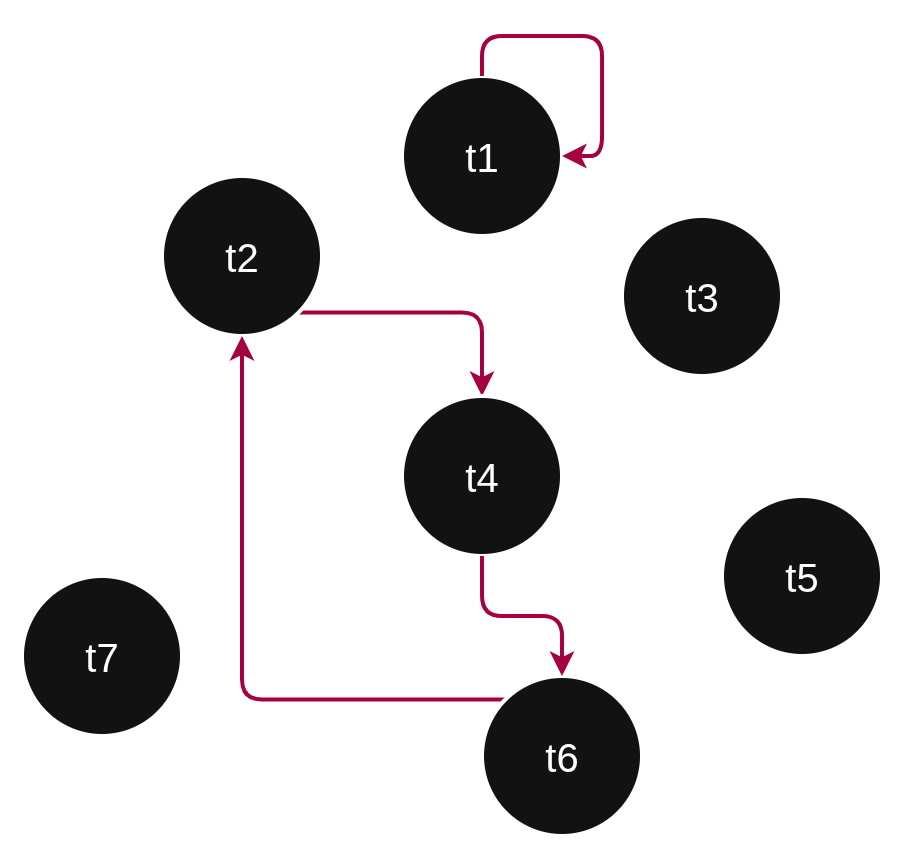

The idea is pretty simple. If we consider waiting tasks as forming a graph in which tasks are vertices and task tm awaiting tn means there is an edge from tm to tn, then we consider a deadlock to exist whenever this graph contains a cycle. Intuitively, a task involved in a cycle of waits can never be done waiting, since it’s effectively waiting for itself to finish waiting.

Figure 1. An example of some waiting tasks. Edges involved in cycles are red. Task t1 is waiting for itself. Task t2 is waiting for t4, which is waiting for t6, which is waiting for t2. With deadlock detection, these scenarios would not be allowed to occur.

Although algorithms are provided in the literature1, enumerating all cycles in a given graph is pretty challenging. Fortunately, the problem doesn’t have to be posed this way. We know that when the pool is created, the graph has with no edges, and the only way to add one is to do a wait. Therefore, rather than studying the whole graph, we can ask a simple question each time a wait is requested: Would this wait create a cycle? For example, when task3.wait(task5) is called, we answer this question by starting at task3 and walking along the edges of the graph, visiting task5 and then whatever task task5 is awaiting (if any), then whatever that task is awaiting (if any), and so on. If there are no cycles, we will eventually end up at a task that isn’t waiting, and we can safely begin the wait. The alternative is that the new wait would create a cycle. In this case, our walk will eventually take us back to where we started at task3. As soon as we notice we’re back where we started, we know a cycle would be formed, and we abort the wait operation. Thus we ensure the waiter graph remains cycle-free.

Note that the complementarity of these two alternatives (eventually hitting a task that isn’t waiting and eventually coming back where we started) depends on the graph never containing a cycle in the first place. If the graph already contained a cycle when we started walking it in this way, there would be a third possibility, which is that we enter an existing cycle that doesn’t contain our starting point. WorkerPool assumes this will never happen, apparently correctly.

Implementation notes

Although the idea is simple, implementing and testing it was not so easy. When wait is called, the first thing we do is check whether the caller is executing a pool task. If it’s not, (for example, the caller of wait could be main()), we know right away that this wait can’t possibly create a cycle in the waiting task graph, because it doesn’t even create an edge. Only a task waiting for a task creates an edge. The implementation uses a thread-local task pointer2 in order to know which task the current thread is executing, if any. From now on, let us assume the caller is in fact executing a task, so we have to proceed with checking for a deadlock.

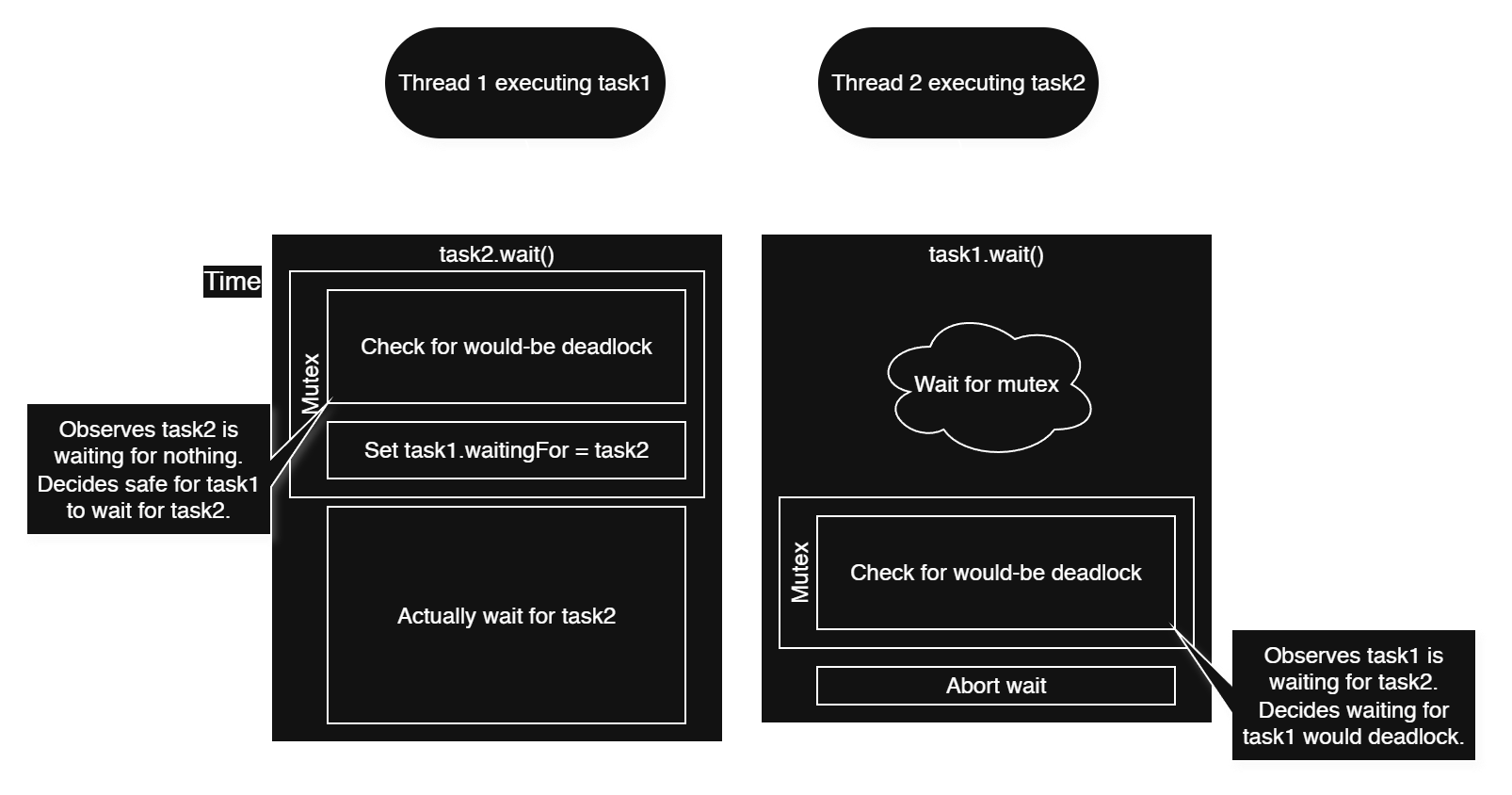

After finding that wait is running inside a task, the next thing we do is lock a mutex that guards the entire process of deciding whether a deadlock is about to form. We then begin walking the graph starting from the task that’s currently executing.

Why a global mutex?

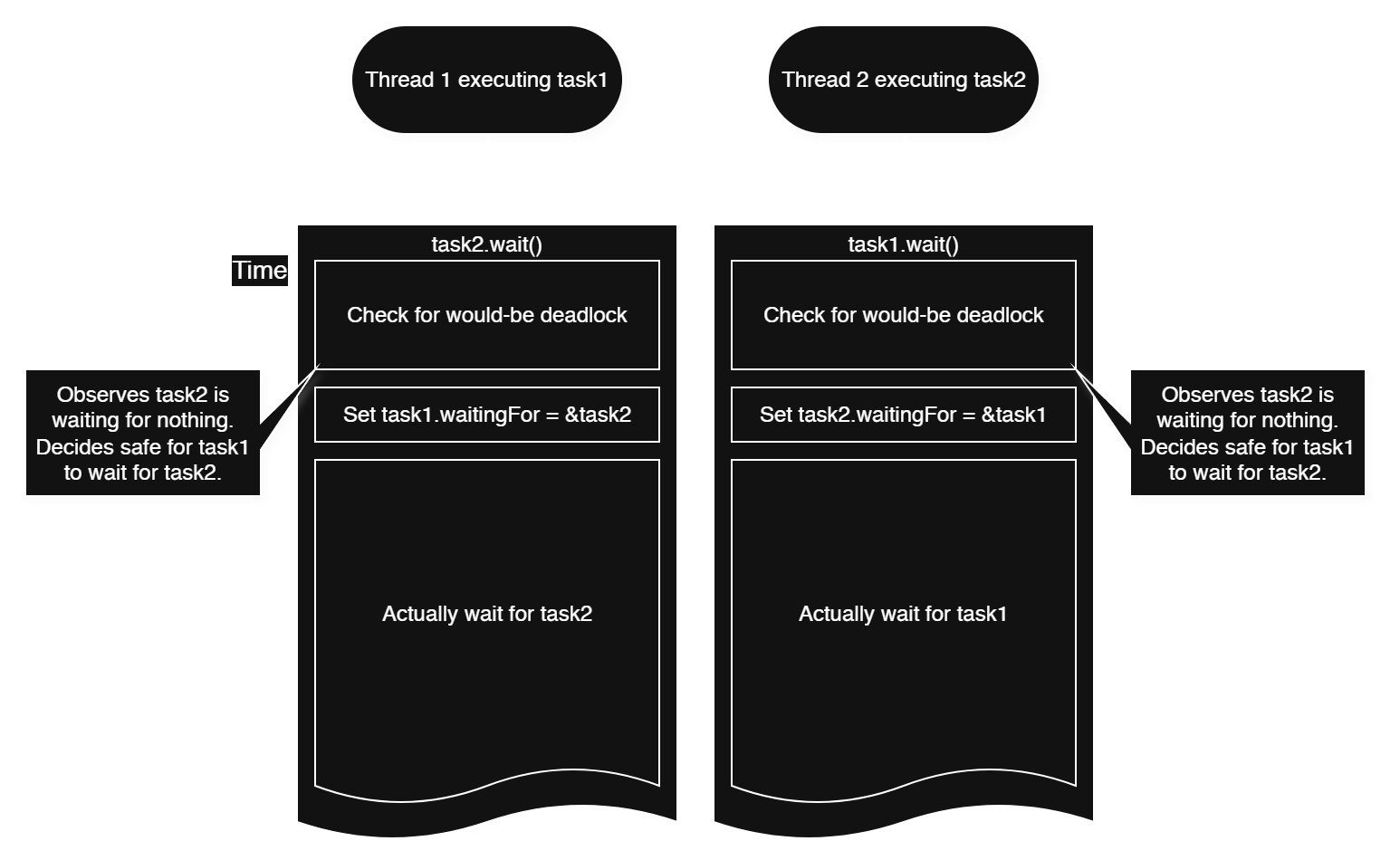

Is a global lock around the deadlock detection procedure really necessary? What could happen without it?

The answer is that we need a mutex around deadlock detection in order to ensure the decisions made by this procedure are visible to other threads in a timely manner. Otherwise, different threads doing deadlock checks and entering waits would race with each other, amounting to a TOCTOU bug.

The deadlock check relies on knowing which task a task is waiting for, so once that information is observed by the check procedure, it must not change until not only after the check is complete, but also after the action guarded by the check is taken.

How do you test this?

The obvious and correct answer is that our tests need to create deadlocks. There’s a variety of ways to set that up, but most of them are not completely correct, nondeterminism generally being a hallmark of asynchronous programming. One must remember that the order of asynchronous operations is never truly predictable until forced to be otherwise. In particular, it pays to remember:

- Threads (or tasks posted to a thread pool) do not necessarily start in the order they were created.

- Thread B can finish before thread A even if thread B started later and had more work to do than A.

Forgetting these facts and making some undue assumptions, I hacked together some deadlock-creating tests that it turned out only worked nearly all the time. When you have numerous waiting tasks in WorkerPool, only the task that attempts to create a deadlock gets an exception–any other tasks that began their wait successfully are unaffected. Those initial tests were flaky because they assumed which task would be the one to deadlock by making the last call to wait. There is a variety of ways to address that, each of which is sufficient on its own:

- Use mutexes/condition variables/atomics to force the

waitcalls to happen in a particular order. - Relax the test’s expectations to encompass any deadlock-involved task, not just a particular one.

- Change

waitcalls toget, sincegetwill throw if the awaited task ends by throwing, whereaswaitwill not. If every task does agetinstead of await, any exception that occurs in one task will eventually be seen by all tasks that transitively wait on the task that originated the exception.

Scaling up the deadlock tests

Constructing a test where two tasks reliably wait for each other is painful enough. For larger test cases, I decided I needed a better way than hand-writing them. Enter WaitCycle, a test helper class I made that generates waiting task cycles of arbitrary size.3

class WaitCycle {

std::mutex mutex;

std::condition_variable taskStarted;

std::vector<std::shared_ptr<task<void>>> tasks;

bool allTasksCreated = false;

std::shared_ptr<task<void>> makeWaiter(pool& pool, int index, int waitForIndex) {

const auto name = std::string("t") + std::to_string(index);

return std::make_shared<task<void>>(pool.add(name, [&, waitForIndex, name] {

{

std::unique_lock lock(mutex);

taskStarted.wait(lock, [&] { return allTasksCreated; });

}

tasks[waitForIndex]->get();

}));

}

public:

explicit WaitCycle(pool& pool, int length) {

if (length <= 0)

throw std::invalid_argument("Length must be positive");

auto indices = std::unique_ptr<int[]>(new int[length]);

auto inverseIndices = std::unique_ptr<int[]>(new int[length]);

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

indices[i] = i;

inverseIndices[i] = i;

}

std::mt19937 engine(1337);

std::uniform_int_distribution<int> dist(0, length - 1);

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

const auto r = dist(engine);

std::swap(indices[i], indices[r]);

}

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

inverseIndices[indices[i]] = i;

}

tasks.resize(length);

for (int i = 0; i < length; i++) {

tasks[i] = makeWaiter(pool, indices[i], inverseIndices[(indices[i] + 1) % length]);

}

{

std::lock_guard lock(mutex);

allTasksCreated = true;

}

taskStarted.notify_all();

}

std::shared_ptr<task<void>> getFirst() {

return tasks.front();

}

};It works by creating length tasks where task i waits for task (i + 1) % length. The games involving indices, inverseIndices, and the PRNG are to ensure we don’t always create the tasks in order from 0 to length. Randomizing the order of creation of tasks means randomizing the order in which they’re scheduled, and this helps verify that correctness doesn’t depend on such order.

We use WaitCycle like so:

TEST(Deadlock, Cycle4) {

pool pool(4, 0, false);

WaitCycle cycle(pool, 4);

auto first = cycle.getFirst();

EXPECT_THROW(first->get(), deadlock_exception);

}This creates a cycle of length 4. Whichever task happens to be the last to (attempt to) wait will be the one that actually originates the deadlock exception. Through get calls, this exception will be rethrown sequentially to all the other tasks in the chain. Thus, for this test, it does not matter which task we call “first” or which one we check the result of. We get an exception whose message helpfully explains the deadlock that would be formed if the wait were allowed:

The requested wait would deadlock: t2 would wait for itself via t3 -> t0 -> t1 -> t2If you ever see this message, this is a reason to give meaningful names to your tasks! Again, in these tests, which task ends up triggering the detection varies from run to run, but the cycle always involves all tasks in increasing order (modulo length) as promised.

Really large cycles: Can we break it?

Incidentally, the largest test I tried had a cycle of 2560 tasks, which works fine on my Linux laptop but overflows the stack on Windows. This is a reminder that Linux programs typically have a default stack size of 8 MB, with 1 MB on Windows. These are not hard-and-fast rules, as both operating systems support other limits. The stack size is typically set ahead of time by the linker, but there are ways to set it when creating a thread dynamically (e.g. pthread_attr_setstacksize, CreateThread). I may consider adding some code to skip these tests if we can’t ensure suitably large stacks, but I’ll likely just keep my test sizes more reasonable instead.

But wait, why would this overflow the stack at all? Is that a bug?

No, it’s not a bug, and no, I don’t use recursive calls to implement the deadlock check4. The reason for the large stack usage is that we have 2560 tasks but far fewer threads, combined with the fact that these tasks do a lot of nested waiting for other tasks. This makes the pool execute the awaited tasks synchronously inside the waiter threads5. In other words, we (the pool) simply push an awaited task onto the stack and execute it. The awaited task eventually tells us to await another task, causing us to push another task, and so on. The worst case is 2560 tasks all executing synchronously on the same thread, and this is evidently too much for Windows with default linker settings and threads as provided by MSVC’s implementation of std::thread.

On said platform, most of the stack looks like this:

worker_pool::pool::add<WaitCycle::makeWaiter::`2::<lambda_1>>::`2::<lambda_1>::operator()()

worker_pool::pool::WorkItem::execute()

worker_pool::pool::wait(shared_ptr<WorkItem>)

worker_pool::task::wait()

worker_pool::task::get()That’s one repeating unit, and I see about 500 of those on one thread. Between the user’s get call (the bottom frame shown) and the user’s callback (the top frame shown), WorkerPool’s implementation is incurring a cost of 3 frames, which I think is pretty reasonable and efficient. If you add up these 5 frames/task × 500 tasks/thread × 40 bytes/frame (assuming the minimum frame size for non-leaf functions on Windows x646), you get 100 kB, falling far short of the expected 1 MB. The remaining stack usage is accounted for by these facts, in descending order by impact:

- Most functions use far more than the minimum possible frame size.

- Although I’m not showing them here, there are about 6 additional frames per

getthat are due to the C++ runtime (essentially glue that sits between WorkerPool invoking the user’s callback and actually entering the user’s code). - Some 500 bytes due to logging.

- Some 250 bytes due to the runtime initializing the thread.

In an optimized build, as expected, we can go a lot further (some 2.5x as far, it turns out) before hitting stack overflow. This is thanks to the optimizer removing some stack variables as well as interprocedural optimizations such as inlining.

- https://doi.org/10.1137/0204007, https://doi.org/10.1137/0205007, https://doi.org/10.1137/0202017 ↩︎

- Pointer to WorkItem really, not task, but I will not distinguish between the two here. (WorkItem is not exposed publicly.) ↩︎

- Incidentally, this is not the first time I’ve generated cycle-containing object graphs for unit test purposes, but it is the first time where “is blocked waiting for” was the relation between the object pairs. ↩︎

- Never implement anything using recursive calls unless the recursion depth grows very slowly like

log(n). Otherwise you’re just writing a toy. ↩︎ - If you’re curious for what reason and under what circumstances WorkerPool executes tasks inside

waitorgetcalls, see the earlier post. ↩︎ - https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/build/stack-usage ↩︎